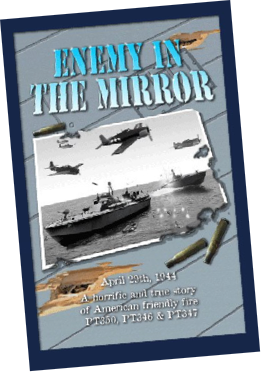

April 29th, 1944

A horrific and true story

of American Friendly fire

PT350, PT346 & PT347

Written by Jo Frkovich

Research materials from

Daniel & Thomas Williams

April 29th, 1944

A horrific and true story

of American Friendly fire

PT350, PT346 & PT347

Written by Jo Frkovich

Research materials from

Daniel & Thomas Williams

PROLOGUE

War is without a doubt one of the worst, most destructive inventions of mankind. It causes pain and suffering on a scale that is truly beyond human comprehension. This was never truer than in World War II, where nearly all of humanity experienced carnage on a scale that was greater than anything that has since come before or after it. Millions died and millions more suffered. In this huge conflict, it can be easy to get lost

in the numbers and lose the personal stories that really put a face on how horrific war can be. One such story

is that of a friendly fire incident that occurred to a small group of sailors off New Guinea in 1944. The story was sad and tragic, but in war those stories are common. As a result, the incident and the men who bravely survived it were almost lost to history; however due to the efforts of the families of some of the victims and

a few survivors this incident will live on as a defining example of honor and courage.

The story was not easy to uncover. As the family of any war veteran will readily tell you, war experiences are held close in the mind of most of those that served. The experiences are often so scarring that just repeating a story can revive ghosts and memories that are simply too painful to remember. This was especially true for Petty Officer 1st Class John Frkovich, who had seen the worst of World War II through the eyes of its victims, spending three years in the Pacific as a Navy corpsman, most of the time based aboard theUSS Hilo, a PT boat tender and the flagship of the PT boats in the South Pacific. Corpsman learned not to become too close to anyone; the pain was too great when a friend was lost and unable to be saved.

John Frkovich was present for the invasion of Guadalcanal and for the other Solomon Island and New Guinea campaigns in the Southwest Pacific. He was there when the Navy and the world was introduced to the kamikaze pilot. In 1944 he was witness, in the span of a month, to all but four of the 26 PT casualties of WW II resulting from friendly fire and rendered emergency medical aid to many of the 27 wounded survivors.

The search for the truth behind these chilling friendly fire incidents detailed in the pages that follow began with an account overheard by his sons on fishing trips where John Frkovich traded war stories with his buddies. John spoke of being adrift in the waters of the Pacific Ocean during 1944 and losing many crewmates after his PT boat was sunk by friendly fire.

One particularly poignant story of bravery helped inspire his grandson, Jimmy Frkovich, to join the military almost 60 years later, with the goal of becoming the kind of leader who protects his men, as the skipper of PT 346 did that fateful day. Busy tending to the wounded, Frkovich searched for a life jacket to put on the skipper, who was mortally wounded. The skipper, realizing he was going to die, in a last unselfish act of leadership, gave the life jacket to Frkovich, knowing that he would not survive in the open sea without one.

The facts in the story that follows, taken from actual testimonies and diaries of the men involved in the friendly fire incidents, paint a graphic and often moving picture of the events that took place that day.

USS Hilo shown before the war, as the yacht, Catherine (left). Petty Officer 1st Class John Frkovich, Navy corpsman (middle), based on the USS Hilo, PT boat tender in WW II (below).

THE SEARCH FOR ANSWERS

With searing Arizona summer heat literally cooking his skin and the refuge of cool water just inches away, what could have kept John Frkovich, a Navy PT boat veteran and a man who loved boating, out of the water for almost 30 years? His friends and family could only wonder. Given his love of boating and the Arizona summer temperatures frequently in excess of 110 degrees, why could John Frkovich NEVER be enticed to enter any body of water?

The story came out slowly in bits and pieces, never fully discovered until 32 years after his death in 1973, when a World War II claim for lost items from PT boat 346 was found in his papers. An internet search for any reference to PT boat 346 quickly filled in the horrific details of an account that had been front page news in many newspapers including the May 4, 1944 editions of the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle.

The New York Times headline, “U.S. Planes Sink 2 U.S. PT Boats; 2 Shot down in Mix up of Signals” was a watered-down account of events that took place in Pacific waters on a clear day, April 29th, 1944. Certainly the death of two Marine pilots and 14 Navy men, all by friendly fire, could reasonably be termed something more than a “mix up”. But it was wartime and accounts of military mistakes would not have been popular. In what is often the irony of war, a horrific toll was taken, not by the enemy, but by the mistakes of our own.

Approximately 20 percent of the casualties on PT boats during WW II in the Pacific were the result of friendly fire, due primarily to the loss of lives resulting from the April 29th, 1944 tragedy and from a similar incident that occurred on March 27th. In the space of only one month, 22 PT men had been killed by friendly fire. These two incidents represented 85% of the total friendly fire casualties on all PT boats during WWII in both the Pacific and Europe.

PT 346 had been involved in both friendly fire incidents, first as a rescuer in March and then as a victim in April. The fact that they were under attack by their own in no way lessens the heroic acts of the men on PT boats 346, 347, and 350 that day as they fought for survival, nor the contribution they made to the success of the war. Large warships were in short supply, and these PT boats were often the only link and sea protection for those fighting on the surrounding Pacific islands and for pilots shot down at sea. The PT’s were called “ the mosquito fleet” and their crews - brave, daring and sometimes reckless - were known for using deadly torpedoes to sink the Japanese fleet with their “toy boats,” and for using their guns to sink enemy barges, cutting off vital supplies to the Japanese troops on the islands.

The search that began in 2005 with the discovery of John Frkovich’s PT boat number, 346, would lead to an internet web site, “Tragedy at Sea,” and to Dan Williams, son of one of the PT boat captains, whose boat and men were also lost in the friendly fire incident that day. His compelling web site provided detailed first hand accounts by his father, Lt. Robert Williams, and other tales of the dramatic events as they unfolded that day. Dan’s cousin, Thomas Williams, obsessed by the impact this event had on the life of his beloved uncle, had doggedly fought to obtain transcripts of the investigation of the incident, including the testimony of the crew involved and personal diaries and accounts given by the men. At the time, the men were given specific orders not to discuss the incident, but to Thomas Williams, the words and personal accounts left a compelling trail of events and broken rules of engagement, a story that had to be told.

THE CHAIN OF EVENTS BEGINS

The tragic day began at in the predawn hours of Saturday, April 29, 1944 when PT boat 347, out on nighttime patrol for the Japanese, headed for the coast of Rabaul and became stuck on a coral reef in the Southwest Pacific. The night was quiet and very dark. The location played an important role in the tragedy, as it was just 3 miles from the line of demarcation, the line that divided the Pacific Ocean into two different areas of command. The PT boats were in an area commanded by General MacArthur (Southwest Pacific Command). The Marine planes, which would subsequently sink the PT boats, should have been patrolling just to the east of their actual location and were under the command of Admiral Nimitz (South Pacific Command).

The war in the Pacific had no supreme commander, unlike the European theatre where Eisenhower was in overall command. In the Pacific theatre, power was shared between Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur. When no one person is in charge, lines of authority are blurred, and communication is poor, the results are often disastrous. In the military the stakes are high, because lives can be lost. Although there were daily dispatches to the South Pacific Command from the Southwest Pacific Command regarding the PT’s whereabouts, they were not relayed to the air units, setting the stage for disaster. Moreover, many of the pilots involved in the PT boat attack reported they had never been told there was a line of demarcation between the two separate areas of command.

PT boat 347 was captained by Lieutenant Robert J. Williams, an Annapolis graduate of the class of 1942. Lieutenant Williams, as a skipper, was greatly admired by fellow officers and his crew, and he should have had a long and prosperous career in the Navy. Although the PT boats had maps of the Pacific, they were often inaccurate and the shoals were not clearly marked. This particular coral reef was not on the maps at all. “Any PT man will tell you that he worried as much about reefs as he did about Japs,” said Lt Commander Hall, USN, whose PT boats had been sunk by friendly fire less than a month before. “You get hung up on a reef near an enemy held shore and you’re a sitting duck.” In fact more PT boats in WWII were lost to reefs, than to enemy fire. Although Lt. Williams did not bear any fault for the events of the day, clearly he could never shake the weight of their burden. He was subsequently early retired a year later from the Navy, partially mentally disabled from post- traumatic stress syndrome.

THE FIRST ATTACK

The tragic chain of events began to unfold during a routine mission by PT’s 347 and 350 to intercept any enemy traffic north or south, around Cape Pomas. Their orders were to destroy enemy barges, ships and shore installations wherever possible. It was a nighttime operation and the boats were to have returned to base by sun up. When PT 347 became stuck on a reef at approximately 2 a.m., PT boat 350, commanded by Lt. S. L. Manning, spent half the night, almost five hours, attempting to dislodge her. Manning later reported, “In all this time, we were unable to get the PT 347 off the reef.” When dawn broke efforts continued, but at great risk as the boats became clearly visible. The risk became life threatening as two planes were identified circling close by and general quarters (the order to assume battle stations) sounded. The planes went into the attack position, so the PT men assumed they were Japanese Zeros.

These two planes were actually United States fighters led by Major James K. Dill, U.S. Marine Corps, part of Nimitz’s South Pacific Command. He had been sent out earlier that morning to attack any targets of opportunity. Four Corsairs headed out, but one plane had engine problems and headed back to base accompanied by his wingman. The two remaining planes had headed slightly off course, now in waters operated by the separate Southwest Pacific command. Having wandered off course, they had no information regarding the PT boats operating in the area. Major Dill’s wingman, Lt. Cochran, spotted two ships ahead, and the planes decided to fire on the targets, heading to 6,000 feet above the targets and well above the reach of anti-aircraft fire. The Corsair fighters were one of the most heavily armed and fastest planes of the time, with speeds over 400 miles per hour. These planes were called “whispering death” by the Japanese due to the low pitched sound the engine made. They also had a very long nose which made landing on a carrier or looking directly below more difficult for the pilots.

The weather was clear and the sea was calm with a visibility that day of 15 miles, yet Captain Dill reported seeing “no recognition signals of any kind.” However, by many of the PT men’s accounts, the planes began firing from two miles away, too far to allow for adequate visual inspection. There is little doubt that a visual by the pilots would have identified these boats as their own. Throughout the attack, PT 347 signaled “S” and “V” with the searchlight and the three officers aboard waved their arms frantically, unsuccessfully trying to raise the pilots using the radio daytime frequency until the last plane disappeared from sight.

Just before 7 a.m. Doc Hirsch and Red Connors, two cooks aboard the 350, were preparing a breakfast of flapjacks, bacon and coffee. Less than 20 minutes later, Doc Hirsch, who had come along just for the ride, would be dead and Red Connors would be wounded, and PT 350, severely damaged and riddled by aircraft machine gun fire would be heading back to base at Talasea, carrying three dead and five wounded. One American pilot would be dead. In the space of a just few minutes and a single strafing run made by two planes, many lives were changed or lost, and an even greater horror would be set in motion.

As the initial battle between the Marine pilots and the Navy PT boats began, some of the men thought the planes were our own as they approached. There was some disagreement regarding whether the planes were friendly; the Corsair fighters were not the typical American fighter planes the men were used to sighting. Were they going to buzz the men? This was a common practice, hated by the PT men. Were they trying to identify the boats? The men were hoping the planes would come near enough to recognize the PT boat’s distinctive silhouette and see the two huge aircraft identification stars painted in blue and white on both the chartroom canopy and on top of the day room canopy, the largest being seven feet in diameter. Several men reported, “All the gear was cleared from these areas immediately when the planes were sighted.” American flags waived from the top of the PT boats masts, forward and aft. PT 350 also started a 360-degree turn to the right as instructed for emergency identification, but Lt. Manning testified, “Before I had completed a third of the circle, the action had begun.”

With smoke coming from the leading edges of the planes’ wings and a path of bullets ripping up the water, headed towards the boats, the PT men knew they were under attack.

PT 35O TAKES HEAVY LOSSES

Once the planes began to fire, PT 350, assuming the planes must be the enemy after all, proceeded eastward into deeper water and opened fire. Radioman Louis Brick sent a message to the USS Hilo, “We are being attacked by planes,” and then the radio received a direct hit, making further transmission impossible. As the two planes were pulling out of their dive, PT 350 blew a hole in one of the fighter’s wings and the plane went down. The pilot, Lt. Cochran, was lost at sea.

The damage log for PT 350 shows how much carnage had been delivered by a singe run of the two Corsair planes. It reads:

“Shrapnel on the port side of 37 mm, hole in the starboard deck and shrapnel marks forward, hole in deck by starboard forward cleat, 2 holes in deck on starboard bow, whole in forward hatch, shrapnel under life raft stowage, 2 holes in 20 mm ready service locker, also exploded one mag and hole in 20 mm handle, 1 20 mm mag creased, 20 mm mag caved in, shrapnel at galley hatch, 2 holes through forward combing on chartroom, 2 holes on top of chart room, shrapnel in 50 caliber turret on forward side, hole in forward torpedo rack starboard, hole through radar breather tube, hole in mag for 30 caliber, 50 caliber on starboard side hit by shell, hole in deck above starboard fuel tank, 3 holes in radar mast, forward starboard torpedo had 20 mm hole in warhead, hole through starboard side of day room, sheared cable on starboard depth charge rack, shrapnel through radar rack, beach casing of 40 mm hit, 1 hole engine room hatch cover, 2 hits on 40 MM ready service locker causing it to start on fire, 2 holes through auto loader cover on 40 MM, shrapnel holes in 40 MM ready box starboard side, 2 holes in aft day room, hole in forward port of day room on port side, 2 hits on deck on port beam, 7 bullet holes in cockpit, hole in port forward torpedo rack, 5 holes on port side of hull, 1 hole forward starboard side hull, 2 hits on aft starboard torpedo, hole in port 50 caliber turret, 50 caliber in port turret hit, blew up 2 37 MM ammunition boxes, and ammunition. Hole in mag for starboard twin 50 caliber mounted between torpedoes, exploding some of the ammunition.”

The damage to PT 350 was extensive. Heavy smoke was pouring from the stern and sheets of flames were coming over the engine hatch. Ammunition was exploding, and the boat was taking on water very rapidly in the engine room. Smoke continued to pour from the crews’ quarters and the chart room. A small fire in the crews’ quarters and a much larger fire in the armory were extinguished with the CO2 system, but the engineers finally got the engines started. PT 350 was ordered back to base. Two depth charges and four torpedoes had to be jettisoned to lighten the ship because of the bad leaks in the engine room to gain some speed. The engine room continued to flood and they were able to drain it aft, but only while underway. It was a difficult trip aboard a PT with extensive damage and over half of its 15-man crew dead or injured.

The heavy smoke over PT 350 caused by the puncture of the smoke screen generator prevented accurate identification of the downed and burning plane. A few of the men thought the attacking planes were American, but most thought they were Japanese Zeros, and that was what was reported to command. The planes had swept around wide and up to an attack position and started in quickly, preventing easy identification. They also were a type of plane not common in the area; the men were used to seeing P-38’s, P-40’s, and P-47’s, but not the Corsair fighters.

PT 346’s RESCUE MISSION

PT 347 had not been fired upon and had not suffered any personnel or material casualties but instead remained stuck on the reef, still a “sitting duck” in the daylight. Lt. Williams took a life raft to deliver medical supplies to the injured on PT 350. One of General MacArthur’s base commanders, Lt. “Red Dog” Thompson, commander of the 25th at Talasea, was dispatched to help PT 347, still on the reef, and to deliver medical aid to the wounded on PT 350. He took out PT boat 346, skippered by Lt. James Burk and carrying Chief Petty Officer John Frkovich and Seaman James Cheek to render medical aid. Lt. Colonel James Petitt, United States Army, also went along as observer. He left the base unaware he would die in less that six hours, perhaps suffering the most brutal wounds of the day.

As a precaution, Lt. Thompson had requested air cover from Cape Gloucester. It turned out that the damage to PT 350 was too extensive for PT 346 to come along side to provide medical aid. PT 350 could not stop without flooding so the men headed out to help PT 347 off the reef, and PT 349 escorted the damaged PT 350 back to base.

PT boat 346, along with PT 354, had been dispatched on a similar rescue mission less than a month before, on March 27th when 8 men were killed and 12 were wounded. Two PT boats (PT 353 and PT 121) burned, exploded, and sank, lost due to friendly fire by five fighter planes under the command of the Royal Australian Air Force. PT 346 and PT 354 had picked up the survivors, many of whom were horribly wounded. Others had severe burns resulting from the wall of flames that came as the boats exploded. PT boats were powered by three modified air plane engines, carried 3000 gallons of 100 octane airplane fuel to propel them, and were loaded with torpedoes and ammunition, making for horrific fires and explosions when they were hit.

Twenty out of twenty-nine aboard the two boats had been killed or wounded. The rescuing crews from PT 346 and 354 loaded up the wounded along with the bodies of the dead, who had been tied to life rafts or stretched out in the bottom of lifeboats along with the injured. The men were in tough shape; many were moaning. The sun was deadly that day and these men had been baking in the brutal heat. They used their helmets to pour water over the injured to provide some relief. The wounded were given morphine shots and made as comfortable as possible and taken back to base.

Approximately one month later, setting course for PT 347, those aboard PT 346 would soon find themselves under similar attack from friendly fire, taking even heavier casualties.

SECOND ATTACK IS LAUNCHED

At the same time General MacArthur’s men were preparing to rescue PT 347, Admiral Nimitz’s men were preparing an all out attack on the gunboats, believing they were Japanese. The remaining Corsair Pilot, Captain Dill, returning to base, radioed that his wingman had been shot down, and that he had strafed two large Japanese gunboats. He radioed, “Order immediate attack!” Colonel C.T. Bailey at Green Island, under the command of Nimitz, held off ordering the attack until he could speak personally with Captain Dill. After Captain Dill landed, he reported the boats were 125-foot Japanese gunboats (PT boats are only 80 feet in length) and heavily armed. He also gave an incorrect location of Lassul Bay. The PT boat schedule from the night before was checked, but for the wrong location.

Relying on Dill’s report, Colonel Bailey then launched an armada of planes in response (twenty-two to be exact), all headed to finish off two gunboats, one immobile on a reef. The planes would not be able to locate the gunboats in Lassul Bay but would be redirected by Captain Dill to the actual location, just North of Cape Lambert and outside of the planes authorized area of operation.

Terror was going to rain from the skies on PT 347 and PT 346 in a few short hours. The earlier morning attack involved two Corsair fighters and a single strafing run lasting only a few minutes, but now an entire squadron (four Corsair F4U fighters, six Avenger dive-bombers, four Hellcat F6F fighters, and eight Dauntless dive-bombers) was on the way. By 2:00 p.m. the two American PT boats would be facing the firepower of more than one hundred 50-caliber machine guns and thirty bombs. This ferocious attack on the men of PT 346 and 347 would continue until 3:30 p.m., or for approximately one and a half hours.

For over a year not one PT boat had been sunk due to misidentification, and since the beginning of the war there had been no PT casualties from friendly fire in either the Pacific or Atlantic. Now, two incidents were to occur only a month apart. The Allies were now able to supply more air cover to the Navy, and many of the pilots were young and inexperienced. “PT boats looked nothing like what the Japanese have,” according to Lt. Commander C.C. Hall, executive officer of the PT boat squadron, who was severely wounded (shot in the knee and neck, broken leg) in the friendly fire incident a month earlier on March 27th. The Japanese gunboats were 60 percent longer, built on a barge platform, and lacked the PT boat’s sleek profile. Perhaps it was inexperience and youth that caused the tragedy. “Put a young inexperienced man in a plane, and he loves to show off,” said Hall. “We have the same problem in PT’s. Some of our young boat captains thought there was no bigger thrill than to jab the throttles all the way forward and tear across the ocean like a cowboy riding herd. We relieved them of command if we caught them.”

Lieutenant Thompson arrived around 12:30 p.m. and began working to pull PT 347 from the coral heads. Around 1:30 p.m., the men heard planes approaching in the distance. The planes were flying in roughly five rows of four planes each. There were high clouds but visibility was good enough to pick the planes out at a distance of ten miles. Lieutenant Howitt and Lieutenant Burk (skipper of 346) inspected the planes with glasses and noticed American markings on them. Lt. Thompson told the crew it was the air cover he had requested. “We have recognized them as friendly planes. They are our air cover. Go back to work. We have to get this done.” The salvage work continued. Both boats were immobile and tied together as the planes approached.

SECOND ATTACK BEGINS

Around 2 p.m. the planes began to circle the area at high altitude and started making their runs. It slowly dawned on the sailors below that these friendly planes were not providing air cover, but launching an all out attack. “The planes had started peeling off to attack us, starting their runs at a distance of six or seven miles from the north,” Lt. Howitt reported. He also heard a voice over the radio say, “All right fellows, let’s go.” Lt. Thompson frantically attempted to contact the planes by radio but had no success. Prior to the attack and during the dive, the radiomen from both boats on the voice circuit called, “This is Sacred,” (meaning we are PT boats), and giving every known plane call signal they could think of – Hydraulic, Frolic, Smutty and Fred (all known fighter calls in the Southwest Pacific). The two PT boats, still tied together, never moved or fired.

But there was never any effort on the part of the planes to identify the PT boats. The planes were too high and too far way, and took no time to look the boats over before beginning their attack. “The planes made no attempt of any kind to challenge or identify the boats and came no closer than six or seven miles before starting their run,” testified Lt. Howitt. Unfortunately, no system of recognition signals can prevent an attack unless aircraft make an effort to identify their targets before attacking and give the boats a chance for their recognition signals to be seen. The boats were covered with three blue and white identifying stars (an additional star had been painted on the cock pit of cover of PT 347 since the first attack), radio contact was attempted over and over, and American flags were flying. PT 347, who was hit earlier that day, had covered her deck with every available American flag; one flying from the radar mask, one from the stern, one especially rigged to hang from the bow and one draped over the engine room hatch; four in total. On PT 346 the officers braved machine gun bullets to hold up an eight foot American flag for identification. Some pilots would later say they saw the flags, but thought it was a trick by the Japanese.

PT 347 EXPLODES AND SINKS

PT 347, an easy, immobile target stuck on the reef, was the first target. Gunner Wilbur Larsen provides this first hand account. “The first bomb overshot the boat (thank God), and hit the reef, which blew coral all over the boat. Some of the boat’s guns were jammed with the coral and out of commission.” PT 347 fired several shots at the attacking planes. The abandon ship order was given by Lt. Williams, saving many lives as in a few short moments there would be several direct hits by bombers and a series of explosions followed by fire, which would completely destroy PT 347. Ensign Couch, third officer, reported she burned and exploded in front of her men.

Gunner Wilbur Larson reported he was one of the last to get off the boat, as he was busy firing his 20-millimeter gun. “A passenger was with us on the patrol, Carpenter Mate Forrest May, and he got off the boat and was standing on the reef yelling at me to come help him, as he couldn’t swim and had one thumb shot off, and he was hanging on to it.” One man, Raymond Juneau, seaman first class, refused to abandon ship and was the first casualty on 347 when the direct bomb hit occurred approximately three minutes after the order to abandon ship and blew PT 347 apart. Little did the men know that their ordeal was just beginning.

Gunner Larsen got the injured non-swimmer, Forrest May, into the water so he would not be such an easy target as the dive bombers continued to try to hit PT 347. His personal account: “They missed a couple of times and finally hit it with the third try. It was raining 100 octane gas from our fuel tank, and I was afraid the PT boat would catch fire, but it didn’t at that time.”

Soon after PT 347 was blown up by a bomb and the men’s situation became even more precarious. Several of the men reported tremendous gasoline fires and explosions and that the boats simply disintegrated. Larsen reports, “After the boat blew up they started strafing us. My non swimmer and I faced each other so we could tell if the plane was lining up with us to strafe us, then we would duck under the water where we could see the 50-caliber bullets swooshing by.” They did it so many times we were exhausted. “Try hanging on to a life jacket at the same time you’re ducking under the water.” Wilbur Larsen would later be awarded the Navy Marine Corp Medal for saving Forest May’s life. He spent the entire time in the water, not only keeping himself afloat but also keeping his non-swimming buddy afloat by pulling him up out of the water and then under again to avoid the non-stop air fire.

Lt. Williams ordered his men in the water to “REMAIN DISPURSED,” and also ordered them to put their helmet on their life jacket and duck under the water as the planes came in. The continual submersion required of the men proved too much for John Dunner of PT 347, who drowned. No one could say for sure if he had been hit. He became the second casualty of PT 347. Robert Valentine reported holding onto his life jacket, swimming under the water when the flames and bullets came, then returning to the surface to find his life jacket shot to pieces. He swam to a smoldering mattress, and hid behind it when the planes came in, again and again, for the kill.

Meanwhile Lt. Thompson, squadron commander who was on the 346, had made every attempt to contact the planes by radio to identify the boats as American, but to no avail. Bomber pilot Major Ernest Hemingway reported hearing a phantom cry, “Planes overhead,” but he attributed it to the fighter pilots.

PT 346 SINKS AND TAKES HEAVY CASUALTIES

The crew of the 346 was at general quarters, but no order to fire was given, and no shots were fired prior to the first run at the PT 346. Lt. Thompson later testified, “I tried to contact the planes by radio. Lt. Burk, meanwhile, had hoisted a set of colors which were approximately eight feet in length.”

Lt. James Burk, skipper of 346, placed himself in the direct line of fire to help identify the PT boat as friendly and save his men. This brave act did not surprise any of the men. The first shots from the planes hit him. Gunner Frank Burns testified, “The planes got Mr. Burk, our skipper, on the first run, so Mr. Thompson went to the wheel while Mr. Haywood, our executive officer, fired our recognition signals. The first bomb was a close miss, which put our engines out of commission and started a fire.” Burns’ station was the bow operating the 37-mm gun, and he reported, “All my ready boxes were shot up on the first run, and on the second, the gun itself was blown from the mount.”

Meanwhile Chief Pharmacist Frkovich gave Lt. Burk, who had been mortally wounded a shot of morphine. During this time bombs were hitting all around the boat and planes were strafing. No one had been prepared for the attack; they thought the approach American planes were their air cover. Many, including John Frkovich, did not have life jackets. John Frkovich searched for a life jacket to put around Lt. Burk, who, realizing he had little chance of surviving, ordered Frkovich to take the life jacket for himself, concerned only for his men as he took his last breathe. Seconds later Burk was gone. Ollie Talley was in the engine room when the first bomb hit, taking out the batteries and tearing up the starboard engine, causing a fire. He came out and saw the planes and Lt. Burk, curled up in the cockpit, dead. Years later when he was told that Lt. Burk had ordered Frkovich to take his life jacket, O J Talley replied, “I am not surprised, Lt. Burk was a great man and would have done anything for his men.”

Gunner Bob Mills was firing away on the forward 20 machine gun, attempting to get the planes to abort. He would later die on the way back to base from internal injuries. Lt. Thompson, with Chief Frkovich by his side, made one last valiant effort to identify the boat as friendly. “I cut the large colors from the mask and stood up on the day room, holding them up so that the planes could see them. Chief Petty Officer Frkovich held up the other end of the colors, directly in the line of the strafing planes, which approached within at least 200 yards while strafing, without giving any sign of recognizing the colors.” Once again this valiant attempt to gain recognition as friendly was greeted with a burst of machine gun fire.

“All guns on PT 346 opened fire when it became apparent that the first planes were going to continue firing at it,” testified Lt. Howitt. After coming under heavy attack, PT 346 shot down a Hellcat F6 fighter (its pilot was later identified as Lt. Knight), which only made the situation worse. Ensign Wilde testified he and some of the other men tried to throw the life raft overboard, but “we saw another plane coming in, so we hid behind the forward torpedo on the port side. Seeing a bomb released I took hold of the railing on the dayroom. It appeared to me that the bomb went through the bulkhead into the crew’s quarters. The explosion lifted the entire boat.”

A second account was provided by Lt. Thompson. “A 1,000 pound bomb passed through the day room and exploded beneath the boat,” he testified. “The boat immediately went into flames, and I dove over the starboard quarter into the water.” Verle Wisdom and Paul Whitmore also reported abandoning ship. Several men reported being blown off the boat into the water: John Frkovich, Frank Burns, J.H. Cheek, and James Alkire. Chief engineer O. J. Talley reported being blown out of his shoes, with a life raft in hand. Witnesses saw the explosion lift the entire boat out of the water. The abandon ship order could scarcely be heard over the roar of the fires and the exploding ammunition. Frkovich told his family he could not have survived the upcoming ordeal in the water that day without the life jacket from his skipper, James Burk. Lt. Williams from the PT 347 indicated he looked over at the 346 and saw her burning furiously, with the TBF’s skip bombing and planes strafing her. Pieces of PT 346, along with many of her men, were blown through the air. Both Lt. Burk, and PT boat 346, the “Betty Bee”, named for Lt. Burk’s wife were gone. But at the moment the men had no time to mourn their loss.

BOMBS AND BULLETS RAIN FROM THE SKY

“After we were in the water the planes made run after run for one and one-half or two hours, bombing and strafing the survivors in the water,” testified Lt. Howitt. “One dive bomber circled three times, about twenty feet from Thompson, myself, and another man, at an altitude of fifteen feet, and I could almost recognize his features if I saw him again. Then I noticed that the bombing planes pulled away and disappeared, but the fighters then came down and continued the strafing of survivors for another hour.” Gunner Verle Wisdom reported being “hit in the right leg, twice, on the last run they made.”

The men of PT 346 spread out to make a poorer target; the planes repeatedly would cut a path almost up to the men, and over and over they slipped off their “Mae Wests” (slang for their life jackets named after the buxom star of the times) and submerged themselves until the planes and .50 machine gun bullets passed by. Shells passed by them in the water and also ricocheted off the water back into the sky. The PT men reported the fighters made several low runs and reported they saw the pilots' faces; some said they could recognize the men again. The unspoken thought was, “Why couldn’t the identify us?”

This awful ordeal continued, in total, for one and a half hours, with the men’s only chance of survival being to duck under the water again and again as the planes approached, holding on to their life jackets for cover. This constant submersion is what gave John Frkovich, and many of the other men, an ongoing aversion to ever going in the water again.

As the casualties mounted for the 346 from the strafing, the men watched helplessly in horror as their friends disappeared, one by one, under the waves, distraught that they were unable to even retrieve their bodies. Lt. James Burk, Lt. Colonel James B. Pettit, Ensign Alfred Haywood, Bill Walters, Ray Reilly, Allen Walzhauer, Leslie Wicks, Stanley Wisniewski of PT 346, and Ray Juneau and John Dunner of PT 347, were all lost to the sea. Ollie “J” Talley reported in his testimony that a final bomb hit on top of Bill Walters in the water. There were several reports of Lt. Colonel Pettit first being shot through the lung while in the water; then, clinging to the raft, his head was blown off by the strafing. Ensign Haywood was also killed in the water by strafing. All three men were seen sinking to the bottom of the Pacific.

The remaining men in the water gazed in the faces of the pilots as they closed in. No one knows for sure what caused the planes to finally leave. Gunner Wilbur Larsen thought one of the pilots finally spotted their red-headed commander, (Lt. Red Dog Thompson). O. J. Talley offers another explanation. He believes his prayers to the Lord were answered that day. Talley was not a religious man at the time, but in desperation he prayed, “Lord, if you could only make it rain, maybe these planes would go away.” It had been a clear day, with only high clouds, but rain DID come. Without radar, the planes could not safely continue the strafing runs; O. J. Talley believes the Lord answered his prayers; after this experience he became a deeply religious man.

When the bullets and bombs finally stopped, the surviving men from PT 347 gathered together, with Wilbur Larsen continuing to tow the wounded non-swimmer, Forrest May, first to a life raft, then over to the reef.

The survivors of PT 346, many of who were badly injured, ended up in a separate location from PT 347. Finally, after the planes had left, they could also safely access their life rafts. “All survivors from the 346 that could be located swam or were assisted to the raft where Chief Pharmacist Mate Frkovich rendered first aid to the nine wounded,” testified Lt. Thompson.

The carnage that day had been monumental: the dead numbered 16: 14 PT men and two pilots. The wounded numbered 17: all PT men. The worst casualties were on PT 346, with nine killed and nine wounded. By the end of the day PT 346 had taken over 1/3 of the friendly fire casualties on all PT boats in World War II. Only two of the 20 men on PT 346 survived without serious injury: Chief Pharmacist Frkovich, and motor machinists’ Frank Burns. Even PT 346’s mascot, an Irish terrier dog named Chopper, suffered shrapnel wounds in the face.

AFTER THE ATTACK

The men continued to float in the waters of the Pacific for about another hour and a half, heading for the reef. The men from PT 346 and PT 347, ending up in different locations, did not know the fate of the other crew until much later. The weight of uncertainty continued for the exhausted men. The voices of the Japanese, who had been watching this self-annihilation from the surrounding shores of the peninsula, could still be heard as they laughed and drank sake on the shore. Would they come out to finish off the remaining men? Several sharks had been sighted earlier; had they been driven off by the bombs and the strafing, or would they be drawn back by the blood?

PT 346 survivors paddled to the beacon on the reef and tied up. The time was close to 5:00 p.m. Not long after, fighter planes, along with a Catalina plane, returned looking for the downed Hellcat pilot. The men fired flares and took off their shirts, hoping that they could be identified as white. “The planes flew close and inspected us, and then the Catalina landed and picked up a survivor from PT 347 that we had not seen (Henry O’Connell), and then picked us up,” testified Lt. Thompson. “The plane had thirteen survivors aboard and took off. More survivors were seen in the water and the plane circled, and I definitely saw two men, but the plane could not land to pick them up as it was already overloaded.”

The plane also spotted the crew of PT 347, circled around and dropped off a 15-man life raft. They would not be rescued until much later that evening. The life raft did not open all the way, but on the way to retrieve the raft, Larsen and Ray Sequin saw the bow of the PT 347 was still afloat and smoldering. The men were able to salvage two lockers in the crew quarters and found a carton of Lucky Strike cigarettes and a can of Almond Roca, and enjoyed the pleasures of this simple find. “We had no dry matches, but paddled over to the burning wreckage of PT 347 and lit a cigarette from the burning timbers,” reported Joseph Cubera. The men chain-smoked, and ate candy that afternoon and evening, still in shock from the two brutal attacks.

THE LAST MEN ARE RESCUED

It was 10:30 p.m. before two PT rescue boats, PT 351 and PT 355, arrived for the PT 347 survivors, to bring them back to base on the USS Hilo. These men had spent almost nine hours in the water. It would take most of the night to arrive back at the USS Hilo at 5:30 a.m. The booze came out of the bilges, according to Wilbur Larsen’s account, and the survivors tried to calm themselves and blunt the horrors of the day on the trip back to base. But, of course, this day could never truly be forgotten by any of the men.

SAYING GOODBYE

The next evening, on April 30, 1944, back at the army base where the USS Hilo and her PT boats were stationed, the few recovered bodies (those that died aboard PT 350 - Raymond Rouleau, Stanley Janusz, and Bill Hirsch) and Robert Mills from PT 346, who died on the way back of internal injuries, would be buried by their comrades. Some thirty men went ashore for the burial services.

The diary of Seaman Dusty Rhodes recorded the events: “The PT men just straggled off, looking all around the place as if they had entered another world and received instructions for the ceremony from the officer. The bodies of our men were loaded on to a truck to be driven to the base of a large, extremely muddy hill we all were to climb. This hill seemed immense. We weren’t used to climbing mountains, not PT men! The men carrying the stretchers had a tough time, but they finally made it to the place where four shallow graves were dug. The scenery overlooking the bay was beautiful, but marred by the misty, overhanging clouds of death.”

“Our boys, the crews of each of the dead men’s boats, lowered the bodies, one at a time, the corpses wrapped in US Navy blankets,” Rhodes diary continues. “There was only silence and grim, sorrowful faces as the bodies entered the graves followed by the echoing of a dull thud. The Chaplain recited his sermon in a low, hardly audible voice, his words ushered out of his mouth like a train pulling out of Grand Central Station. There was an all hands salute, and the bugler sounded taps, and our boys started shoveling, some fast and furious, others slow but furious, sweat on our foreheads, trickling over our eyes and into the graves, doing what they would have done for us.” His toast to the men being buried, “May the aroma of peace fill your unbreathing heart and may it know the great music that is still to be written in this world you so suddenly left behind.”

The sorrow in Seaman Rhodes diary is palpable as he buried two of his closest buddies: Bob Mills, “the man who was my second brother since we first meet in Boston,” and Doc Hirsch, a talented and well-loved musician. Doc had a blond mustache, friendly smile and kept the men entertained, regaling them with stories of the two weeks he spend auditioning on Broadway, where he hoped to return some day. As Rhodes is burying Doc he tells him, “You were all I ever wished my unborn son to be.” Rhodes spots Doc’s head of wild brown hair peaking out from under his burial blanket, and laments the loss of Doc’s voice, his music and his laughter. “My eyes on Doc’s - can’t seem to get them off the brown moist earth, gradually covering the form that was the Saxophone King.” Recalling the days of liberty in Panama - the nights in the cooks’ shack celebrating Christmas and New Year’s Eve with six quarters of rum - the memories and loss flooded through him as he buried his friends.

COPING WITH THE LOSS

PT boaters lived in close quarters, and the loss of these men was like the loss of family. The men were ordered not to talk about the incident except aboard the USS Hilo, their PT boat tender, but of course, the two terrible friendly fire incidents, only one month apart, resulting in the death of twenty-four men and the wounding of twenty-five more, were burned into the memory of all PT men from that time forward. “Whenever friendly planes appeared, we wondered whether they recognized us,” reported Edgar Hoagland, author, The Sea Hawks: With the PT Boats at War.

The loss of the men was difficult for the pilots, as well. PT men were their rescuers when the pilots were downed at sea, and after these rescues the pilots and PT men often became close friends. The USS Hilo was a converted yacht, and because of this it had two bathtubs. The pilots would make frequent trips to Sydney for rest and recreation (R & R), and often returned to the USS Hilo with a bottle of scotch under their shirts for the PT men to trade for a bath, a soft bed, and all the cold water they could drink. These PT men and Marine pilots were not strangers; they were real friends.

INQUIRY INTO THE INCIDENT

Rumor among the PT men was that General MacArthur raised hell about the incident and leaked it to the press, and that Nimitz responded by declaring that “no Marine will be indicted, prosecuted or penalized due to this tragic accident,” which in fact was to be the case. These two men were locked in a political battle, which MacArthur would ultimately win, for overall commander of the Pacific to lead the invasion of Japan.

The four day formal inquiry into the incident found that James K. Dill, the major who initiated and led the attack, made the following errors in judgment: unauthorized crossing of the line of demarcation, leading an aircraft attack against friendly surface forces without attempting in any manner to identify them, and extremely careless navigation. However, no action was taken against him. He later retired from the United States Marines as a full Colonel.

Many of the pilots testified they had not heard of the line of demarcation or did not know where it was. First Lt. R. P. Lewis, USMCR, “I had never been briefed on the location of the line of demarcation.” First Lt. Dickson, USMCR, “I did not know where the line was.” First Lt. Badgley A. Elmes, USMCR, “I was not briefed on the fact that there was a dividing line between SoPac and SoWestPac.” First Lt. William J. Barr, USMCR, “I had heard about the line, but never knew where it was.”

Often, despite the best of intentions, we fall short of perfection. On April 29th, 1944, this had disastrous consequences. It was clear from pilot testimony that the command center had relied too heavily on the inaccurate reports of Captain Dill, and that the pilots had relied too heavily on the orders of their command center rather than making their own identification. Major Ernest Hemingway, in charge of the bombers involved in the strike, had inquired if these boats could be Peter Tares (PT’s) and was told to keep a lookout for any identification but was assured that ComAirSols had taken all necessary precautions before sending the order to strike immediately. He also stated, “Any fears I might have had about faulty identification were dispelled by the continued low altitude strafing runs by the fighters.”

The top secret, May 11, 1944, reports to the Secretary of the Navy from the Commander of the Seventh Fleet found the boats took appropriate actions to be identified as friendly, that “no attempt was made, or time given by the planes, for identification of the boats” and that the boats “had no choice but to defend themselves.” The report concluded, “The personnel of PT 346, 347, and 350 are to be commended for their conduct under fire aboard the boats, and while being strafed in the water.”

RECOMMENDATIONS OF INQUIRY

Major recommendations and changes were made to the rules of engagement as a result of this tragedy, which did contribute to the future safety of the PT men. Three of the most significant were:

1) That all PT boats and aircraft in the Pacific be equipped with VHF radio so that positive voice communication could be established at all times between the PT’s, gunboats, and friendly aircraft.

1.2)That all air commands thoroughly familiarize their pilots with the following: location of lines of demarcation, aerial photos of allied PT’s and gunboats as viewed from various altitudes, aids for identification employed by allied PT’s and gunboats, operating areas currently in use by allied PT boats and gunboats.

3)That during daylight pilots refrain from attacking or assuming hostile position from altitude until a positive identification of the boats can be made. The panel ruled that the delay involved in doing this is negligible and would result in little loss of opportunity for making a successful attack due to the relatively slow speed of the surface target.

A TRIBUTE TO THE MEN

This tribute was written to the men who perished and were wounded. It is from the diary of Dusty Rhodes, USNR seaman and ship’s cook aboard the USS Hilo, home base for the PT’s. His words were born from the anguish of the day:

“The names of the men killed and wounded, or where they came from is of utmost importance to those they were the closest to him - the mother that bore him, the father who supported him and loved him until the end, and of course, the girl he was to marry - the unborn sons who will learn to love him in the future. These are the people who sorrow the most. At night when everyone else is asleep, I pray for these people. I pray silently within myself, that these good people of the world keep faith and love in their hearts, for it is the survivors of this universal catastrophe who must and will see the dawn on the horizon.”

Below are the names that Seaman Rhodes asks us to remember. The following lists the servicemen on board PT’s 346, 347, and 350 on April 29th, 1944. Of the 50 PT men on the three boats that day, 14 were killed, 17 were injured, and 19 survived the ordeal without physical harm; however, no one was untouched by what happened that day.

PT 346 (9 killed, 9 wounded, 2 unharmed)

Killed:

Lt. James R. Burk USNR, Skipper, (KILLED)

Lt. Colonel James B. Pettit, United State Army, aboard as observer, (KILLED)

Ensign Alfred W. Haywood USNR, (KILLED)

William Neal Walters USNR, seaman first class, (KILLED)

Robert West Mills USNR, ship’s cook second class, (KILLED)

Raymond Russell Reilly USNR, torpedo man’s mate second class (MISSING)

Allen Frederick Walzhauer USNR, gunner’s mate third class (MISSING)

Leslie Wilson Wicks USNR, seaman first class (MISSING)

Stanley Wisniewski USNR, quartermaster third class (MISSING)

Wounded:

Lt. James R. Thompson USNR, Commander Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 25

Lt. Eric M. Howitt Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve, pilot officer

Norman Alfred Nadeau USNR, gunner’s mate second class

James Phillip Alkire USNR, motor machinist mate second class

James Harold Cheek USNR, pharmacist mate second class from USS Hilo (shot in the hand)

Verle James Wisdom USNR, yeoman second class (hit twice in the right leg)

Paul Eugene Whitmore USNR, radioman second class (shot in the left leg)

Ensign Gustav Walter Wilde USNR, third officer aboard PT 346

Ollie “J” Talley USNR, motor machinist first class (torn cartlidge in knee, shrapnel behind ear)

Unharmed:

John Frkovich USNR, chief pharmacist mate of the USS Hilo, aboard 346

Frank Joseph Burns USNR, motor machinist second class

PT 347 (2 killed, 3 wounded, 10 unharmed)

Killed:

Raymond Theodore Juneau USNR, seaman first class (KILLED, refused to abandon ship)

John Harry Dunner USNR, coxswain (DROWNED)

Wounded:

Lt. (jg) Robert J. Williams USN, skipper

Henry Paul O’Connell USNR, gunner’s mate second class

Forrest May USNR, carpenter’s mate second class

Unharmed:

Lt. (jg) Eugene G. Clayton USNR, second officer

Ensign Franklin L. Couch USNR, third officer

James D. Sizemore USNR, quartermaster third class

Dean K. Whitmore USNR, radioman second class

Robert Carpenter USNR, torpedo man

Joseph A. Cubera USNR, motor machinist’s mate third class

Bernard J. McGee USNR, seaman first class

Raymond A. Sequin USNR, torpedo man’s mate second class

Robert J. Valentine USNR, seaman second class

William B. Larson USNR, motor machinist’s mate third class

PT 350 (3 killed, 5 wounded, 7 unharmed)

Killed:

Raymond Arthur Rouleau, USRN, motor machinist mate second class

Stanley John Janusz USNR, gunner’s mate third class

William Edward Hirsch USNR, seaman first class

Wounded:

Harold William Connor USRN, ship’s cook second class

William Frederick Reilly USNR, gunner’s mate third class

Robert Ambrose Gaynor USNR (member of 347) machinist mate second class

William L. Brick USNR, radioman second class

Henry G. Westervelt, USNR, gunner’s mate second class

Unharmed:

Lt. (jg) Stanley L. Manning USNR, boat captain of PT 350

Lt. (jg) Baber N. Howell USNR

Harry J. Nicholas USNR, motor machinist’s mate second class

Raymond F. Walk USNR

Clyde W. Wilder USNR, torpedo man’s mate second class

Howard H. Hemphill USNR, motor machinist’s mate first class

Kenneth J Joyce USNR, motor machinist’s mate second class

EPILOGUE

This story was written in loving memory of John Frkovich. He enlisted January 9, 1942, almost immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and spent three years in the Pacific during World War II, serving in the battle of Guadalcanal and other Solomon Island and New Guinea campaigns. Based on the USS Hilo, he often went out on PT boats to care for the wounded and ill at sea and on shore.

Malaria, dengue fever, dysentery and battle fatigue also took their toll, often killing more men than actual battle. Having malaria in the Pacific four or five times was common, and the sick men could not be sent back home, as there would be no one left to fight. The threshold for evacuation was having malaria TEN times!

John Frkovich sometimes traveled with Lt. John F. Kennedy on PT 109. Both men were fluent in Spanish, and Kennedy would often request Frkovich so they could practice Spanish together. After Kennedy became President, Frkovich told his family that JFK would have recognize him if they had met again because of the many hours they spend conversing in Spanish at sea.

Normally, discharges were based on time seen in combat. However, medics were in such great need that this criteria did not apply to them; they were sent over and over into combat. Even though he had seen active duty throughout the Pacific since the beginning of World War II, John Frkovich had received his orders and was preparing for the invasion of Japan in 1945.

President Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan saved him and many others from facing almost certain death from the invasion of Japan. Even after the war had ended, while others were discharged and returning to the quiet of civilian life, the medics continued to serve for months afterwards, treating the wounded and ill back in stateside hospitals, once again face to face with the destruction and awful aftermath of war.

World War II memories and stories abound, but there are almost no first hand accounts from corpsmen, or “aid men”. A search of the internet and WW II books provided this haunting first hand glimpse of the weight these men carried:

"Few people are aware of the personal sacrifices the aid men went through. We were not strangers with the platoon we served with, everyone was a comrade. And unlike the other members of the platoon who can't stop to aid a wounded buddy, they have no idea how it tears the aid man apart to witness one of his buddies wounded and helpless. We eat, sleep, laugh, and yes even cry with these comrades; we become a family, and like any family, death affects us all. But more so because it is the aid man who remains with the wounded until he can stabilize the wounds and have him delivered to the battle aid station. I can never describe the feeling you get when you see your closest friend dead from his wounds, knowing that you were unable to save his life. But it has one advantage; you learn not to become to close to anyone, because the pain is too deep when it was a friend who had died.”

“You have to remove every emotion in your body, or end up a raving madman. No one can ever understand that unless they themselves lived it. In every war history book you read, there is never a description of what the aid man truly feels, and you never will see one. That is why I have chosen to give a detail account of the pain and sorrow that the aid man lives with every single moment of the day. It isn't the acts of the aid man that becomes important but rather the inner pain that he carries within himself; a pain he dare not show publicly, for to do so you risk the probability that others may see that pain, or (fear) which would demoralize the men who puts their trust in your hands.” Albert Gentile, Company B, 333rd Infantry.

John Frkovich was a gentle and soft-spoken man; someone who did not know him well might not realize the steel that lay beneath the surface. He came from hearty stock that did what was necessary to survive and provide for his family. His father, Stanilaus Frkovich, was a first generation immigrant. Hearing the Cossacks were just a village away, he traveled over 300 miles on foot with nothing but the clothes on his back across his homeland, Croatia, to reach a ship to America. He was just ahead of the soldiers from the Ottoman Empire who were conscripting all young men for their war. Arriving in America, he worked in the coal mines of Gallup, New Mexico, until he was in his 60’s. Once he was trapped in a coal mine collapse and survived, with a severely dislocated shoulder. Well aware of the hundreds waiting to take his place in the mine, he immediately returned to work, having his wife tape his shoulder each day for over a year. He continued to work despite the debilitating pain to provide for his family.

Perhaps, due to his father’s example, John Frkovich also continued to work when diagnosed with rheumatic fever and ordered to bed rest or risk heart damage, grateful for his pharmacist job in the years after the depression. This may have contributed to his early death of a heart attack at age 55. He gave his heart to his family and to the men he served, and saved many lives in the South Pacific. Proudly, his legacy lives on, as does the legacy of the men of PT boats 346, 347, and 350, to whom this story is dedicated.

Bibliography/Works Cited:

Associated Press. “Two PT Boats, Two Planes Lost in South Pacific Error.” San Francisco Chronicle. May 4, 1944, page 1.

Bulkley, Robert J. Jr. At Close Quarters: Pt boats in the United States Navy. Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962, pp. 232-234.

Hoagland, Edgar. The Sea Hawks: With the PT Boats at War. Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1999, pp. 89-91.

Naval Historical Center. Friendly fire statistics. http://www.history.navy.mil/index.html

Official Naval Documents obtained under Freedom of Information Act: Report of Action of PT Boat 350, night of April 28-29, 1944; Memorandum to all Hands, J. Paul Austin, USNR, Intelligence Officer; Order Directing Investigation; Investigative Conclusions & Recommendations, Commodore T.J. Moran, USN, Investigating Officer; Statement by Major Dill; Damage report for PT 350; War Diary of Marine Aircraft Group Fourteen.

Oral Interviews: Ollie “J” Talley, Dan Williams.

Personal Written Accounts and diaries of the following individuals: Forrest May, Cromwell C. Hall, Dusty Rhodes, Joseph Cubera, and Albert Gentile.

Peter Tare [online] http://www.petertare.org/nav.htm

PT Boats, Inc. [online] http://www.ptboats.org/

Testimony of the Crew of PT’s 346, 347, & 350. May 3-May 5, 1944. Crew members testifying: From PT 346: Lt. James R. Thompson USNR, Commander Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 25; Lt. Eric M. Howitt Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve, pilot officer; Norman Alfred Nadeau USNR, gunner’s mate second class; James Phillip Alkire USNR, motor machinist mate second class; James Harold Cheek USNR, pharmacist mate second class from USS Hilo; Verle James Wisdom USNR, yeoman second class; Paul Eugene Whitmore USNR, radioman second class; Ensign Gustav Walter Wilde USNR, third officer; John Frkovich USNR, chief pharmacist mate of the USS Hilo, aboard 346; Frank Joseph Burns USNR, motor machinist second class; Ollie “J” Talley USNR, motor machinist first class. From PT 347: Lt. (jg) Robert J. Williams USN, skipper; Henry Paul O’Connell USNR, gunner’s mate second class; Forrest May USNR, carpenter’s mate second class; Lt. (jg) Eugene G. Clayton USNR, second officer; Ensign Franklin L. Couch USNR, third officer; James D. Sizemore USNR, quartermaster third class: Dean K. Whitmore USNR, radioman second class; Robert Carpenter USNR, torpedo man; Joseph A. Cubera USNR, motor machinist’s mate third class; Bernard J. McGee USNR, seaman first class; Raymond A. Sequin USNR, torpedo man’s mate second class; Robert J. Valentine USNR, seaman second class; William B. Larson USNR, motor machinist’s mate third class. From PT 350: Harold William Connor USRN, ship’s cook second class; William Frederick Reilly USNR, gunner’s mate third class; Robert Ambrose Gaynor USNR (member of 347) machinist mate second class; William L. Brick USNR, radioman second class; Henry G. Westervelt, USNR, gunner’s mate second class; Lt. (jg) Stanley L. Manning USNR, boat captain of PT 350; Lt. (jg) Baber N. Howell USNR; Harry J. Nicholas USNR, motor machinist’s mate second class; Raymond F. Walk USNR; Clyde W. Wilder USNR, torpedo man’s mate second class; Howard H. Hemphill USNR, motor machinist’s mate first class; Kenneth J Joyce USNR, motor machinist’s mate second class.

United Press. “U.S. Planes Sink 3 U.S. PT Boats; 2 Shot Down in Mix-up of Signals.” New York Times, page 1.

Wanapela, Justin. “Victims of Friendly Fire- PT 347 & 346” [Online] Available

http://www.pacificwrecks.com/walkabout/rabaul/ptboat.html

White, Maury. “USS Hilo” [Online] Available http://www.usscabildo.org/cabildousn/

thestory.html

Below: Petty Officer 1st Class John Frkovich aboard PT346